- Upon completion of its visit to Peru, the group of experts from the United Nations gave a press conference and revealed its findings

>> En español

After 30 years, they returned to Peru; they encountered a different State and society, but they are also concerned about the slow progress on Human Rights, especially on the issue of forced disappearances.

The United Nations Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances visited the country June 1-10, 2015. Upon the conclusion of its visit, the group gave a press conference in which it announced its initial observations. The Argentinean Ariel Dulitzky, who heads the Group, pointed out that the current situation in Peru is different: we are now in a democratic context and the systematic policy of violation of human rights has been abandoned. However, he expressed concerns: “It is urgent that the Peruvian government set as an immediate priority the search for the truth about the fate and whereabouts of forcibly disappeared persons.”.

The United Nations Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances visited the country June 1-10, 2015. Upon the conclusion of its visit, the group gave a press conference in which it announced its initial observations. The Argentinean Ariel Dulitzky, who heads the Group, pointed out that the current situation in Peru is different: we are now in a democratic context and the systematic policy of violation of human rights has been abandoned. However, he expressed concerns: “It is urgent that the Peruvian government set as an immediate priority the search for the truth about the fate and whereabouts of forcibly disappeared persons.”.

Houria Es-Slami, the group’s expert, stated that 30 years after their last visit to Peru, this delegation found a transformed country: “Since the year 2000, important steps have been made to ensure that the truth, justice, reparation and memory about enforced disappearances that occurred during the political violence between 1980 and 2000 have taken place.”

Both recognized the work of the Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación (Truth and Reconciliation Commission), the creation of the Vice Ministry of Human Rights and the Office of the Ombudsman. But they also expressed concern on the slow progress in the search for the disappeared. The Group urged the Peruvian government to meet the challenge of having a precise number of disappeared persons, to implement a national search plan to identify the missing, a map of mass graves and of genetic data bank. “In the current situation, the relatives will have to wait decades to know the location of the victims”, Dulitzky said.

Here, we share the ten conclusions of the UN Working Group on Forced Disappearances in Peru:

1. The Group appreciates the substantive information that several authorities, the Ombudsman, civil society organizations, as well as victims and their family members provided it with the goal of having a better understanding of the phenomena of forced disappearances in Peru.

2. Thirty years after its first visit, the Group has found a completely transformed country and society. In particular, the state policy of systematic violation of the human rights, including forced disappearances, has stopped. Also, the country has, with great effort, prevailed over subversive violence, although at a high human cost. However, deep scars and wounds remain open.

3. Since the year 2000, there have been important steps to ensure truth, justice, reparation and memory about forced disappearances committed during the political violence between 1980 and 2000. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the hundreds of exhumations, identification and return of remains, the monetary, education and health reparations for victims, the creation of the Vice Ministry of Human Rights and Access to Justice, the role of the Ombudsman, a specialized justice system that has imposed significant but few convictions, as well as the construction of memorials, represent concrete and valuable progress.

4. These advances have been achieved due to initiatives promoted or carried out by families of the victims or by the civil society and some sectors within the state. In accordance with its obligations under the [Universal] Declaration [of Human Rights] and international law, the state must assume those responsibilities and a leadership role to ensure that these initiatives are part of a comprehensive, coherent and continuous state policy on behalf of the victims and their families. Such obligations clearly reinforce the repudiation of [the practice of] enforced disappearance. In particular, the armed forces must make a clear commitment to cooperate in the search for truth and justice. This would strengthen the foundations of a state that will not permit that such serious violations be committed in its name. Given the deep impact that disappearances had on Peruvian women, all activity related to forced disappearances should take into consideration a gender perspective. The international community should support Peru in these initiatives through the provision of funds, training and technical assistance.

5. Thirty years after these forced disappearances, it is concerning that, despite some progress, the efforts to clarify what happened to the disappeared have been very slow and limited, leading.to the clarification of just a few cases of enforced disappearance. This situation has left the families of the victims in a state of permanent uncertainty and prevented them from healing their wounds, as was widely observed during the visit. Investigating these cases should be a priority for the state and part of any process of truth, reparation, justice, memory and reconciliation.

5. Thirty years after these forced disappearances, it is concerning that, despite some progress, the efforts to clarify what happened to the disappeared have been very slow and limited, leading.to the clarification of just a few cases of enforced disappearance. This situation has left the families of the victims in a state of permanent uncertainty and prevented them from healing their wounds, as was widely observed during the visit. Investigating these cases should be a priority for the state and part of any process of truth, reparation, justice, memory and reconciliation.

6. Other important challenges remain. In particular, the Working Group observes with concern that, despite the progress accomplished in the fight against poverty, the deep socio-economic inequalities, which were both the cause and the consequence of the political violence, persist today, preventing the success of many of the adopted measures. Furthermore, there are other specific challenges, such as the lack of an exact number of forcibly disappeared persons, the small number of judicial processes that have come to fruition, the slow progress of legal procedures, the lack of a national plan to search for the disappeared and a national map of graves, the limited number of exhumations and identification of missing persons, lack of comprehensive psychological care received by the victims, and the absence of a public policy on memory issues, among others. The adoption of a general law for searching the missing persons and assignment of an adequate budget for its implementation could help to overcome many of these challenges.

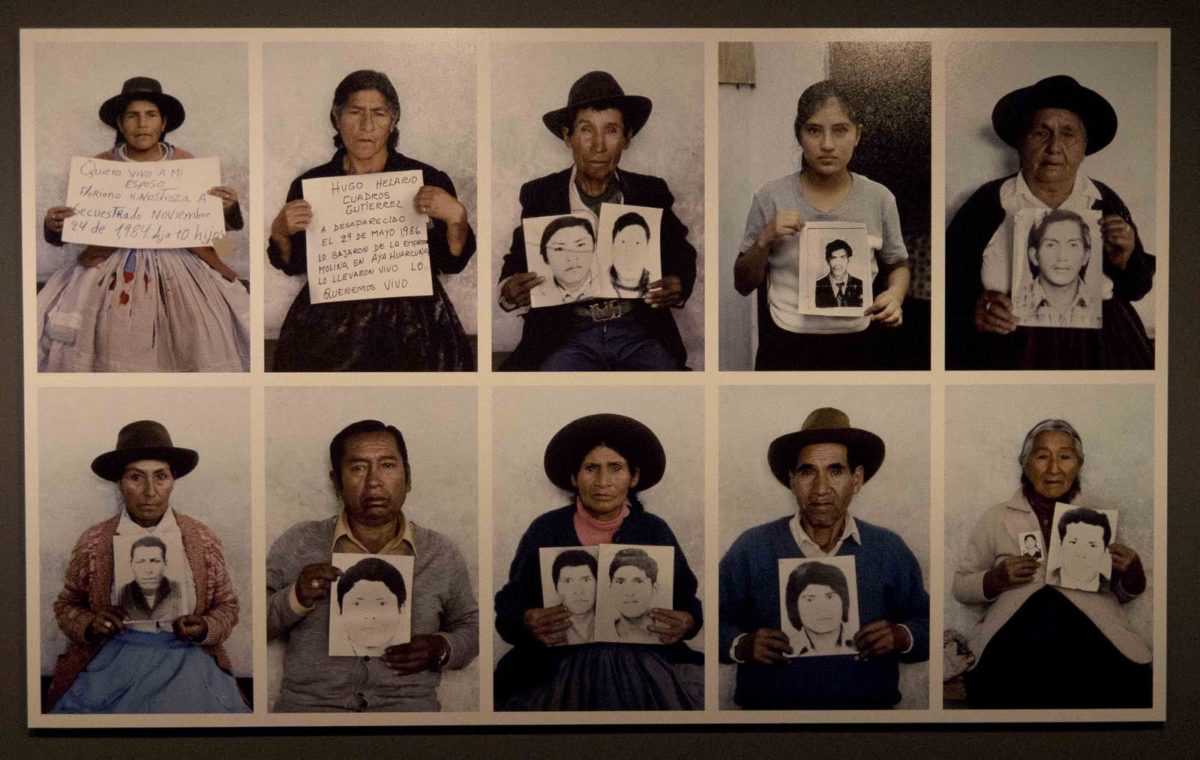

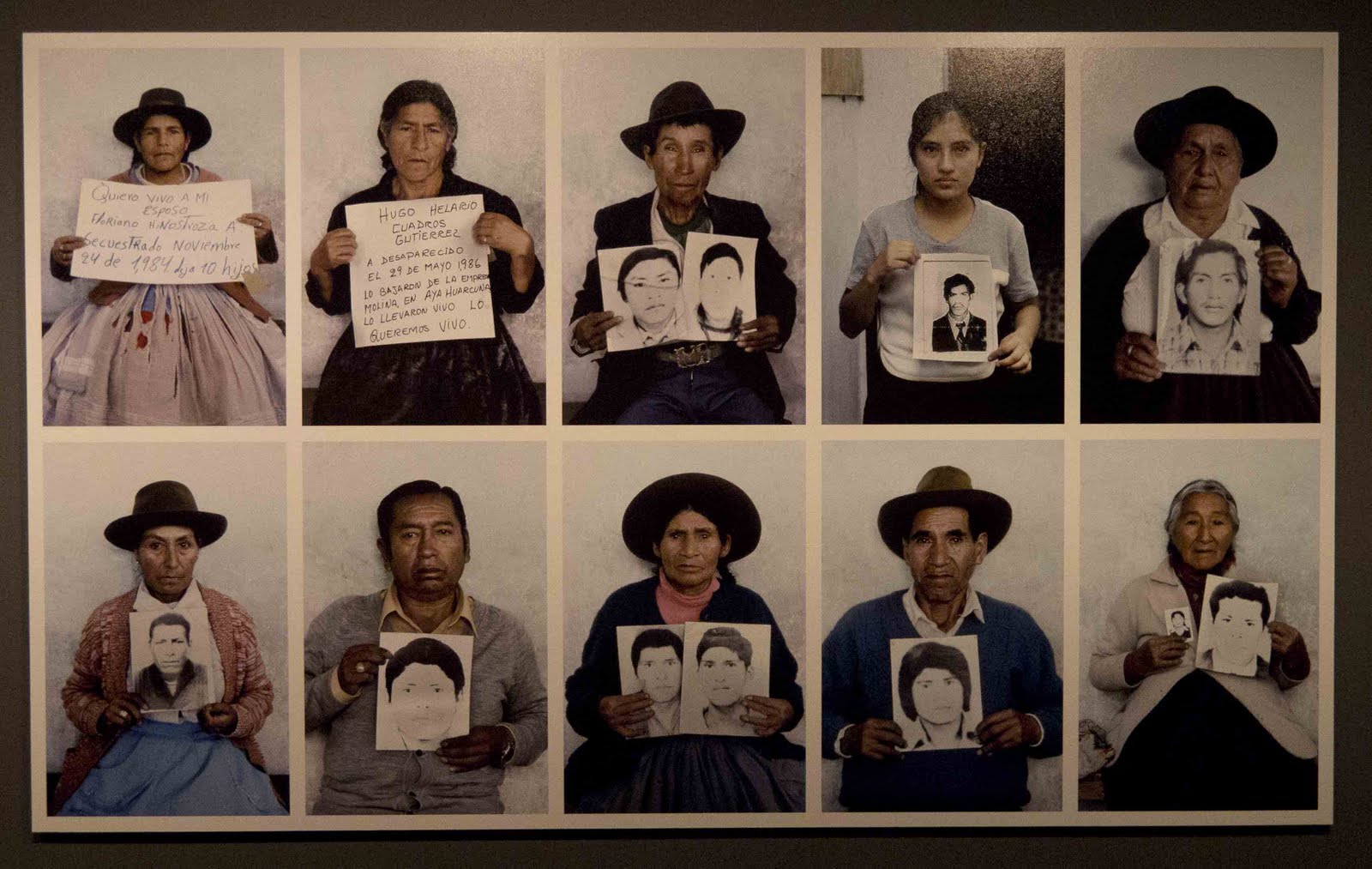

7. In every place it visited the Working Group has met with dozens of relatives of the victims. Virtually all of them have expressed deep frustration over the obstacles and difficulties in accessing the information needed to clarify the fate and location of their loved ones. In particular they indicated that their status as speakers of Quechua and other native languages, as well as their socioeconomic status, make them face discrimination and contempt by the authorities. Given the time that has passed since the majority of forced disappearances occurred and the advanced age of many witnesses, perpetrators and family members, it is urgent that the state adopt the search for the truth and fate of the disappeared as an immediate priority. While in some cases it is difficult to establish the fate of the disappeared person, there is an absolute obligation to take all the reasonable and efficient measures to find the person or clarify their whereabouts. With the same sense of urgency, the state must proceed with the process of justice and integral reparations for the victims.

8. The Working Group reiterates its solidarity with the victims of enforced disappearance and their families. Their constant suffering is the tangible proof that forced disappearances constitute a permanent offense and an ongoing violation of human rights until the fate and the location of the victims has been clarified.

9. The Working Group also recognizes the work of the many human rights defenders, NGOs, lawyers and others who work tirelessly, often in adverse conditions, to bring the perpetrators to court and to repair and preserve the memory of the victims of this terrible practice. Because of that, the Group makes a call to the State and to the international community to provide continuous support to the work of these stakeholders. With this spirit, the Working Group encourages all actors in this area —state, civil society and relatives of the victims— to strengthen their collaboration to bring together all the resources and synergies in a cooperative, concerted and coordinated manner.

10. The Working Group expresses its readiness to continue the constructive dialogue with the Peruvian state and offers its assistance in the full implementation of the [Universal] Declaration [of Human Rights].

Translated from the original Spanish by Eliana Carlin Ronquillo with Karina Arango/ Rights Peru Project (www.rightsperu.net)

Originally published in La Mula June 10, 2015